“I’m a Midwest guy, and I used to miss the snow, believe it or not. I don’t anymore.” Tim Schroeder says as he looks through the window of his home and workshop, greeted by the characteristically bleak Chicago weather—in this instance, a classic case of October snow. He recalls his early years as an apprentice in San Francisco, doing his first guitar repairs for the likes of Joe Satriani and the Grateful Dead. It was there that he was exposed to the people and techniques which would later serve him throughout his career as owner and sole crafter of Schroeder Audio equipment. Now a well-known and well-respected brand of amplifiers used by countless notable artists from Andrew Bird to Jeff Beck to Wilco, Schroeder’s formative years were much less lucrative.

“I didn’t have any skills, didn’t have any capital. I had like, nothing going for me for the most part except for enthusiasm, which [Laughs.] doesn’t get you very far if you don’t have the other things, you know?”

With a thinning wallet, minimal experience, and an abundance of passion, Schroeder decided to leave his home in Chicago and drive across the country, his parrot riding shotgun, in the hopes of finding work in California’s audio world. He talks about these rough beginnings with enthusiasm and an unspoken understanding that no other path would have satisfied him. Though it wasn’t particularly pretty, it is evident that a life not married to music and audio would have been out of the question.

Schroeder’s love of electronics and sound dates back to his time in high school, where he started playing guitar and experimenting with 4-track tape recording. He still owns the stereo receiver he first enjoyed music through, an ancient Mcintosh that used to belong to his older sister. When it appeared to have finally kicked the bucket, his sister opted for a more modern machine, but Tim was happy to take the Mac and get it working again. He still cherishes the receiver and the way his vinyl collection sounds through it. “It’s just glorious sounding to me.” Schroeder says. “It’s super musical and colored in all the right ways.” Tim has always been an audiophile—someone who invests a sometimes scary amount of thought, effort, and money (think $7,000 for a speaker cable) into improving the quality of the music he or she listens to. He attributes this hobby firstly to his acute aural ability, as he can literally hear the difference between varying brands of electrical outlets. He says it’s “a blessing and a curse, of course, focusing on electrical outlet sounds instead of hearing music, but [he’s] always been really motivated to build and be creative with electronics and pretty much anything that makes sound.”

This motivation, along with a since-forgotten nostalgia for Chicago snow, is what led Tim back to the city to continue building his skill set. He found an opportunity to shift from repairing guitars to building them when he met and studied with Bob Benedetto, a legendary luthier of archtop guitars. After learning the finer details of wood selection, carving, and setup, Schroeder started his own shop in 1991. He built guitars as well as a reliable client base of musicians who would often leave truckloads of bizarre ’50s audio equipment for Schroeder to fiddle with in his spare time. It was from these experiments that he first found inspiration to make his own amplifiers. One model, the Schroeder Audio Small Block, remains hugely popular to this day. “After that people just started to find me,” Schroeder says.

“I think the Wilco guys had one amp that no one could fix, and I did it in like, a day or something. They had racks of broken stuff and I was on retainer basically for a month, just fixing everything they had, which is all still working!”

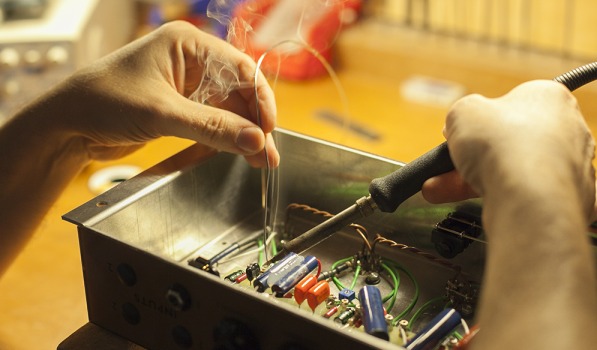

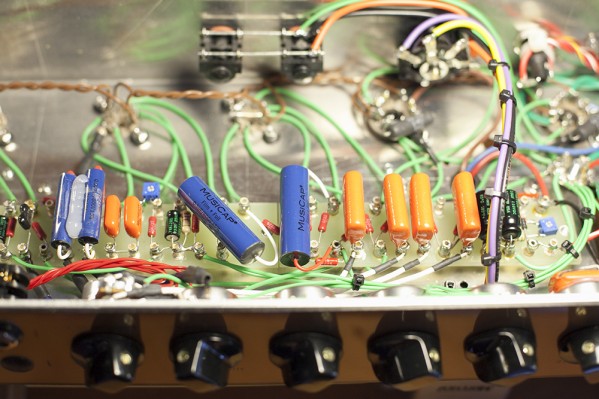

And Schroeder’s meticulous ear shows no signs of fatigue. In fact, his newer equipment sounds even better than the old stuff. The design of his current DB9 model took years to perfect, and he is constantly tweaking microscopic details for improvements in the amp’s sound. From the precise placement of the holes on the chassis, all the way down to the lacquer on each individual wire, “it all makes a difference,” Schroeder says. “The proximity of every single thing in the amp makes a difference. Literally the routing of every single wire makes a huge difference. Even the evolution from the DB7 to the DB9 is just arranged differently to get rid of a small piece of wire. That one switch and little piece of wire makes a big difference, and it does take a long time to prepare. There’s things that I started 12 years ago that I’m still working on.”

For Schroeder, however, it’s essential to be mindful of the difference between meticulous and analytical. When fine-tuning an amplifier, he says it’s important to pay attention to detail, but without letting analysis get in the way of sound. If something’s got “the magic,” as he calls it, that should always reign supreme. “There are certain capacitors that I’ll plug in and analytically think, ‘This one sounds better.’ Schroeder says. “But when I put the other one in for a side-by-side comparison, even though it doesn’t sound as good, after 20 minutes I realize that I haven’t been listening to it at all, and I’m just playing—just kind of in that zone. And that’s the one that wins.” It’s a strategy that has proven to be fruitful for him, as Schroeder amps stand in a league of their own when it comes to sound quality. They offer a pristine clarity that isn’t lost with volume—an unfortunate sacrifice many other amps are forced to make. The unique Schroeder amp sound signature is thanks in part to his history as a luthier. He noticed that many of his beautifully clean archtop guitars were being played through shitty, colored amplifiers. Seeing an opportunity, he started working on appropriately transparent amps for his sensitive instruments. The rest of the sound signature of a Schroeder amp can be credited to Schroeder’s mold-breaking mentality. The last thing he wants is for his equipment to sound like someone else’s. He admits that much of the reason he makes amps in the first place is “for [himself], to try and make something that isn’t available yet.” Even if it’s a sound that he likes, he won’t make it if it’s identical to another product on the market. With that said, Schroeder is not without his influences. He praises Carr amplifiers as well as Bogner. He prefers any amp with transparency over one with coloration.

“I want the guitar to do the talking instead of a piece of gear that’s limiting in some way.”

Schroeder sits at his desk, equipped with his hilarious working glasses, and studies the guts of a new prototype—it’s one he can’t discuss just yet, but he offers a hint. “It’s something I’m working on for Jeff [Tweedy].” He recalls a prior project he worked on for Tweedy, meant to be a surprise gift. When one of Tweedy’s favorite recording amps, a beaten up, near-death Supro, came into Tim’s shop for yet another repair, he decided to make an exact (but working) replica down to the wire. “I blueprinted the entire thing, every single voltage, resistor, the proximity of everything, and made him an exact replica of that amplifier, but, you know, a solid version,” he smiles, “I didn’t tell anybody, I had been working on it for two months and it was going to be ready the next day. I got a call from The Loft and they said, ‘Hey, remember that amp that came in? Can you make an exact replica of that, but make it like, functional?’ and I said, ‘It’ll be done tomorrow.’”

Though his life revolves around music, when asked about his own pursuits as a musician, Schroeder doesn’t have much to say. He’s equally dismissive toward questions about his hobbies outside of audio gear: “I’m not sure,” he says, laughing. “I’m still trying to figure that out.” A true artist, Schroeder seems totally content to be consumed by his passion. He shares pictures of himself as a youth, licking guitars owned by some of his idols: Albert Collins, Bobby Weir, Jerry Garcia. “I went through a guitar-licking phase” he says with both pride and nostalgia. He insists that he isn’t a weirdo. His meticulous ear and superhuman attention to detail may seem a little crazy, but to Schroeder it all makes sense. He asserts that “everything is a tool and everything has its place… Including non-Schroeder equipment, believe it or not!” A worldview like that, while sometimes hard to justify, is without a doubt a healthy one to have—for audiophiles and non-weirdos alike.