Imagine walking down the street listening to The Smiths. As Morrissey croons his misery, that empty bench on the side of the road seems unbearably depressing; that solitary man smoking a cigarette is probably facing an existential crisis.

Now, imagine walking that same path listening to the energetic beats of The Strokes. The empty bench is now inviting and the smoking man nods in appreciation. By changing the soundtrack to one’s life, they can have a completely different set of experiences. In the same way, for a sound designer like Adam Marks, the music he creates to accompany a video game influences the mood of the players.

Marks got his start with sound design two and a half years ago, at the age of 19, when he entered a 48-hour game design competition with his friends. Realizing that the game had no soundtrack, Marks offered to compose one because of his background in electronic music.

“All of us had no idea what we were doing. We just sat down and were like, ‘We’re going to teach ourselves everything in this 48-hour period.’ So we made a game from scratch, learning everything in the process, and that’s what really got me started on this,” Marks says.

When composing music for a game, Marks has to determine what emotion the creators are trying to make the players feel. Then, he finds a genre that will evoke the particular emotion, listens to it for hours on end, and writes a similar tune that will loop in the background of a game.

“I basically force myself to listen to a genre for a good couple hours straight until there is nothing else in my head except for those notes,” Marks says.

“After that, I pretty much just vomit out the music by hitting my hands on the keyboard because the only thing I can play is stuff that sounds like that.”

Depending on the game, Marks may have to write music on completely opposite ends of the spectrum. For a game in which players defend Santa Claus from invading aliens, Marks electronically remixed “Deck the Halls,” while a murder-mystery adventure required a creepy, dramatic feel that he created using “super tragic, Russian folk music.”

Though his composition caters to the whims of his clients, Marks doesn’t feel that his creativity is stunted, but rather that having a set of explicit boundaries points him in the right direction.

Sometimes, he’s composing for his peers rather than a client. The Global Game Jam is an annual competition in which participants in over 200 locations have 48 hours to build a game from the ground up that pertains to a specific theme. Similar, though smaller, competitions occur in the Chicago area, such as one that took place Sept. 28-30 with the theme “To Win is to Lose.” Marks tries to attend at least two of these competitions each year to practice his craft and network within his field.

“On my team, none of us knew each other at the time we got there, but after 48 hours, we’ve all become good friends. It’s a really good bonding experience and a really good way to meet new people.”

Besides writing the music for a game, a sound designer will often create sound effects as well. Many sounds are created in surprising, inventive ways due to a strange phenomenon of the business.

“The most interesting thing with sound design is that if you make the sound exactly like it actually sounds, people will say that’s not it,” Marks says.

“Someone asked me to make a seagull sound once, and I recorded the sound of an actual seagull. And they’re just like, ‘That’s way too low-pitched to be a seagull. It should be a lot higher and squeakier.’”

Marks’ work with sound effects is similar to the job of a Foley artist creating sound for film. However, Foley art is the acoustic version of Marks’ electronic approach.

“Foley art is something that’s done using entirely human sounds. It’s just the sound of a zipper, or the sound of clothing, which is something that most people never notice,” Marks says. “In every single movie, there’s always the sound of clothing when there are people moving, so there’s always a Foley artist who has to sit there with a microphone, just rubbing his shoulder.”

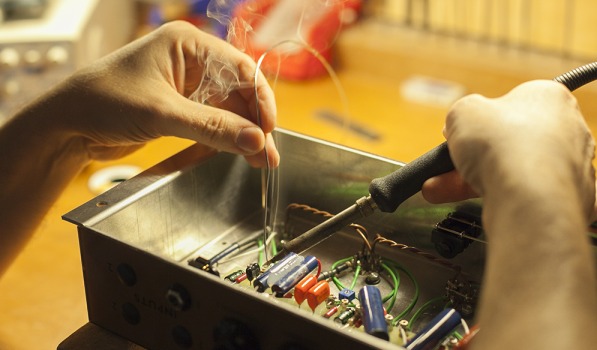

In contrast, Marks uses a great deal of digital enhancement. For example, he created the sound of a crane by recording a door opening, the sound of a gunshot by recording a book hitting the floor, and the sound of a whale by recording himself yelling. The recordings are digitally manipulated, pitches are lowered, echoes are added, and the end result often sounds very little like the original recording.

“My favorite thing to do is put everything through a guitar distortion pedal. I found that it makes everything sound so harsh and edgy that no matter what you run through, it’ll come out really different,” Marks says.

Though sound effects are Marks’ favorite part of the job, the music is considered a crucial factor. However, the music in a game is actually designed to go unnoticed. It’s an element that should, ideally, affect the player’s mood without intruding too much into the game. Therefore, game music tends to be minimalistic, which is exactly what Marks enjoys writing.

Seven years of drum lessons gave him a firm grasp on structure and rhythm, but as far as creating music electronically, Marks is entirely self-taught. He writes music in a very “mathematical” way, following a formula where the rhythm, chords, and melody vary with each song, but always appear in the same order. However, he is able to identify which elements make a genre sound the way it does and apply those to his music in order to evoke the emotion he’s after.

From “Space Lobsters: The Uprising” to “Mr. Rogers’ Revenge,” Marks has contributed to a wide array of eccentric games, all requiring a unique soundtrack to encapsulate the right mood. Much like the music one listens to while walking down the street could completely change the way they feel, Marks’ work adds a crucial element to each game: the element of emotion.